Former K-State faculty plant seeds for the future with new endowed chair

A passion for discovery: That’s what fuels Barbara Valent and Forrest Chumley.

The retired K-State College of Agriculture faculty members spent their careers nurturing curiosity and focusing on problems that stretch far beyond the boundaries of campus. Now they’re fueling the next generation of faculty research.

Their story is one of partnership — both in life and in science. Valent and Chumley met as postdoctoral fellows at Cornell, each bringing their own brand of scientific passion to the table.

“We arrived within two weeks of each other,” Chumley recalled. “I was working on bacterial genetics, and Barbara was already thinking about the big questions — how to tackle plant diseases that threaten food security worldwide.”

Their shared vision led them from the Ivy League to DuPont and eventually to Manhattan, Kansas, where they’ve become champions for basic research and faculty support.

Seeds of discovery

Basic research, also known as foundational research, is the bedrock upon which scientific breakthroughs are built. Unlike applied research, which seeks immediate solutions to practical problems and often ends with a product, basic research explores the unknown. Researchers ask questions that may not yield answers, or products, for years.

“Applied research is vital, but basic research is what gets us places we don’t know we’re going to yet,” Valent explained. “It’s how we solve problems we haven’t even imagined.”

Yet, as both point out, the landscape is shifting. Companies have become more focused on short-term gains, often at the expense of long-term innovation.

“The reason we left DuPont was that they left basic research,” Valent said.

The university advantage

At K-State, Valent and Chumley found a home for their passions. Universities are places where curiosity is nurtured, where the next generation of scientists is trained, and where the boundaries of knowledge are pushed. As the nation’s first operational land-grant university, K-State has long embodied the ideal of conducting groundbreaking basic research that’s powerfully coupled with transferring new technology to the field.

Valent, a plant pathology researcher, was the first K-State faculty member to be inducted into the National Academy of Sciences, which is the scientific equivalent of winning an Oscar. Her research dealt with the ancient blast disease of rice and the emerging blast disease of wheat. Since 1985, wheat blast has caused billions of dollars of destruction in South America, South Asia and southern Africa. Valent’s research focused on finding ways to improve crops’ resistance to the fungi that cause these diseases, which in turn helps ensure global food security. One specific goal was to develop resources to keep wheat blast out of the U.S. and Kansas, which has so far succeeded.

Chumley’s career bridged research and industry. He helped create the Kansas Wheat Innovation Center, the Kansas Wheat Alliance and Heartland Plant Innovations Inc. He was the first president and CEO of HPI and served as the senior advisor of science and special projects with the company.

“I was very interested in the business side of things,” Chumley said. “Part of the sustainability challenge is generating enough revenue to support plant breeding and variety development, especially as it becomes more expensive to use modern research tools. I was excited to form new alliances with producers and private sector partners in ways that enabled K-State to share appropriately in the value we add.”

Today, the Kansas Wheat Innovation Center stands prominently in K-State’s Edge District as evidence of that vision’s success. In addition to the Kansas Wheat Commission, it houses the Kansas Wheat Alliance, a public-private partnership that generates more than a million dollars a year in new funds for university research and development programs.

More than a job

Behind every K-State breakthrough are faculty members whose dedication drives research and teaching. Yet the life of a faculty member is demanding.

“It’s a huge, 24-hour-a-day job,” Valent said. “To do research, you must have money, which comes from grants. Applying for grants is a lot of work, and sometimes you don’t get the money, so you have to start all over again.”

Grants support research, but they also support people — graduate students and post-docs who are vital to conducting research and who also need to learn research techniques. And then results must be published, which is vital to getting new grants.

“And if you’re working with plants and fungi, you have to take care of those organisms,” Chumley explained. “From the time we started working together at DuPont, we worked seven days a week if we had something happening in the lab. You could take a break for a few days, but real vacations were few and far between.”

At a university, another key role for faculty is training the next generation of scientists.

“Barbara got some teaching awards because she took her teaching as seriously as she took her other responsibilities,” Chumley said.

“When you’re teaching, you don’t want to teach the same thing every year,” Valent explained. “Cutting-edge research changes. So every time you have the course, you’ve got to update it to keep up with the latest research.”

Investing in discovery

Recognizing the challenges faculty face, Valent and Chumley decided to invest in an endowed chair to support plant pathology research at K-State.

“Our guiding principle is that knowledge is power,” Valent said. “We want to promote other smart scientists and help them do creative discovery.”

The chair provides flexible funding so faculty can pursue new ideas without the constraints of traditional grants.

“It’s like seed money for when you’re getting started on an idea,” Valent said. “With grants, you have to show the research will succeed, which can be hard if you haven’t been able to work on the new idea yet. This funding will promote creativity because it’s money that doesn’t come with strings attached.”

Chumley stressed that it’s vital for K-State to award more endowed chairs.

“You look at big research universities, and they have a lot of endowed chairs,” Chumley said. “We have colleagues at other universities who have endowed chairs, some of whom are Nobel Prize winners. With more endowed chairs, big opportunities will come to K-State.”

Valent and Chumley are confident their new chair will make a difference.

“Research is not a job. It’s a passion, a life,” Valent said. “This chair is a way to let some of that passion go in a new direction.”

The Barbara Valent and Forrest Chumley Chair in Plant Pathology is a call to action to support discovery, invest in faculty and nurture the curiosity that drives progress. Because in the end, it’s not just about the research — it’s about the people who make it possible.

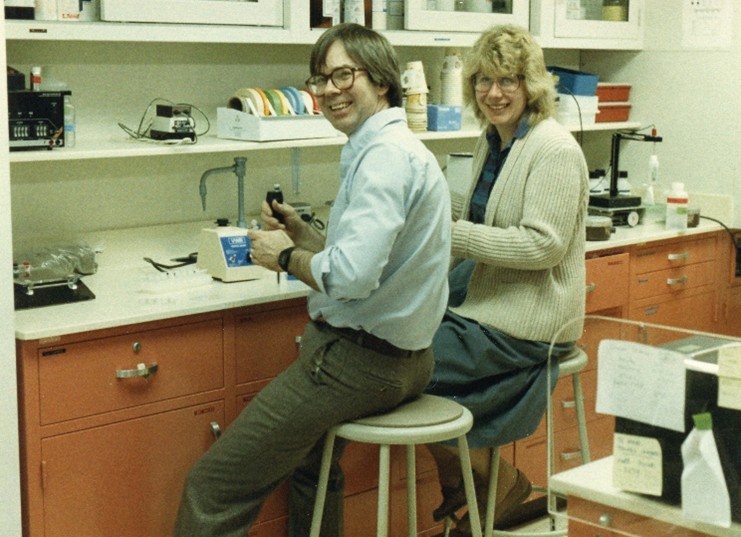

Forrest Chumley and Barbara Valent at DuPont in 1988.

Forrest Chumley and Barbara Valent, retired K-State faculty.