Having benefited from an investment in their education, the Wiltfong brothers and their family create a scholarship to support future rural veterinarians

The actions of one person can have a profound impact on many.

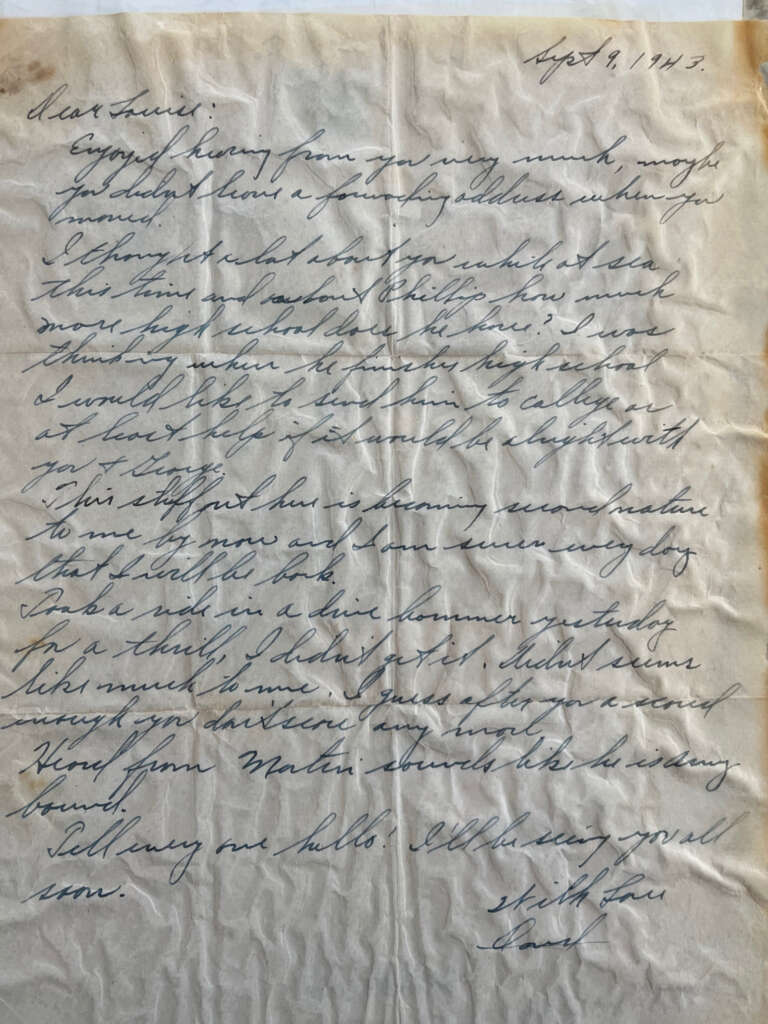

It’s doubtful that David Butler knew what he set in motion in 1943 when he wrote his sister, Louise Wiltfong, that he wanted to help send his oldest nephew to college, if it was alright with her.

Ensign David Butler fought and died in World War II, serving on the USS Tullibee in the Pacific. He’d made Louise the beneficiary of his life insurance, which she used to send all three of her sons to college, fulfilling David’s wish.

Because of his generosity, three generations of the Wiltfong family have attended college, many at Kansas State University. Butler’s three nephews — Phillip, Meredith and Richard Wiltfong — all attended K-State and graduated with doctorates of veterinary medicine.

“Without that life insurance money, those boys probably would have stayed to work on the family farm in Norton, Kansas,” said Cathy Lacy, daughter of Phillip. “However, Louise was very stuck on education, and she would have found a way.”

Now, the Wiltfongs’ passion for education is being used to support future veterinarians far outside the family circle.

A rural crisis

Phillip and Richard set up their mixed-animal veterinary practices in rural areas — Aurora, Nebraska, for Phillip, and Richard in Norton, Kansas. Meredith joined a small animal practice in Omaha, Nebraska, then started his own house-call veterinary service. The brothers not only took care of the animals in their towns, but they were also leaders in their communities, serving on school boards, holding elected local government positions and participating in service organizations. Their lives highlighted the way rural veterinarians are vital to the health of a region.

But today, rural communities, farmers and ranchers are facing a crisis: There aren’t enough food-animal veterinarians.

Being a large-animal vet is hard, physical work. They have to drive long distances and be on call nearly 24/7. And they aren’t paid as much as urban, companion-animal vets.

Beyond being important to their communities, rural vets are vital to the global food supply chain. Without them, diseases such as foot-and-mouth and swine flu could wreak havoc.

“There is no state that does not express concern for access to veterinary care in rural parts of the state,” explained Dr. Bonnie Rush, Hodes family dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine. “In Kansas, starting salaries in rural practices are $20,000 a year lower than salaries in Kansas City or Wichita. If we can help students with an interest in rural practice to have less educational debt at graduation, choosing a career in a rural setting is more feasible.”

Over the past five years, K-State has been able to reduce the debt load of veterinary students by more than 25% through cost-saving advances and increased scholarship support. But vets still graduate with a lot of debt to repay — $95.9K for in-state students and $187.9K for out-of-state students.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the mean annual wage of Midwest veterinarians in 2022 was $84,700 to $115,310. Do the math — new veterinarians will be paying down their debt for a long time. And that can limit their ability to buy into a practice, buy a house, set down roots and start a family.

Paying it forward

Inspired by the letters David wrote to Louise and hearing about the need to ease the debt burden for future rural veterinarians, the Wiltfong family pooled its resources to address the issue head on. Together they created the Wiltfong Brothers Scholarship in Veterinary Medicine for students who intend to practice mixed- or large-animal medicine in rural communities. The scholarship will award a minimum of $20,000 a year, and once it’s fully endowed, it can award two scholarships of $20,000 apiece.

Phillip, Meredith and Richard all met their wives at K-State. Combined, they had 14 children, all of whom went to college (five to K-State), and many who met their spouses there. The third generation — 23 grandchildren — also all went on to college. And all of this was made possible by the veterinary practices the Wiltfong brothers created thanks to their uncle’s generous investment in their education.

Phillip and Meredith have passed. But their wives, Shirley (Wood) Wiltfong and Patricia (Draney) Wiltfong, and Richard and his wife, Marcia (Patracek), and the brothers’ children contributed to the scholarship. The family gathered for a reunion and surprise awarding of the scholarship before a home K-State football game this past fall.

Filling a void today

Melissa Hill grew up in bucolic Manchester, Connecticut, but K-State’s reputation brought her 1,466 miles to study in Manhattan.

What drew her here? The clinic she worked at before veterinary school was owned by two vets who graduated from K-State.

“They’re absolutely brilliant veterinarians. They also brought their pride in K-State back with them, and I knew anyone who maintained that much love for their school must have a reason why,” Hill said. “Also, the year prior to my application cycle, I had some friends who applied and interviewed at K-State, and when one of them came back after her interview, she said, ‘Melissa, you have to apply to K-State. It is YOUR school.’ From then, I was pretty set on attending and with a little luck, I got an acceptance letter!”

The cost of getting a veterinary degree has weighed heavily on Hill’s mind ever since. She knew it meant taking on a lot of debt and that being a rural vet meant it would take longer for her to pay back her loans. But she wouldn’t consider being an urban companion-animal-only vet.

“I just don’t think I would be happy being inside all the time,” Hill said. “And I couldn’t imagine never being able to work on cows again.”

And while she already has a job lined up with Southern Hills Veterinary Clinic in southwest Iowa when she graduates in 2024, Hill remained stressed about paying off her loans.

Then she was invited to attend the pregame event with the Wiltfong family, which ended with a wonderful surprise — receiving the inaugural Wiltfong Brothers Scholarship.

“I was so surprised, honored and shocked! This scholarship helps tremendously because it helps take a bit of that stress away,” Hill said. “When students say anything helps, it really means just that. Any way we can decrease our debt will increase our quality of life, not only while in vet school but also when we graduate. Scholarships for those going into rural practices are so important. These are the areas that really need veterinarians, and scholarships help students go to these places and make a difference in the lives of animals and people alike.”

Make a difference

Are you inspired to be like the Wiltfong family and make a difference in the lives of veterinary students? Learn more here.