What’s the key to making K-State a top destination for elite educators?

Danish physicist Niels Bohr flipped the meaning of success on its head when he said, “An expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field.”

With that nugget of wisdom, the 1922 Nobel Prize winner highlighted an important caveat of scientific discovery: Achieving success is mostly the result of time and dogged perseverance.

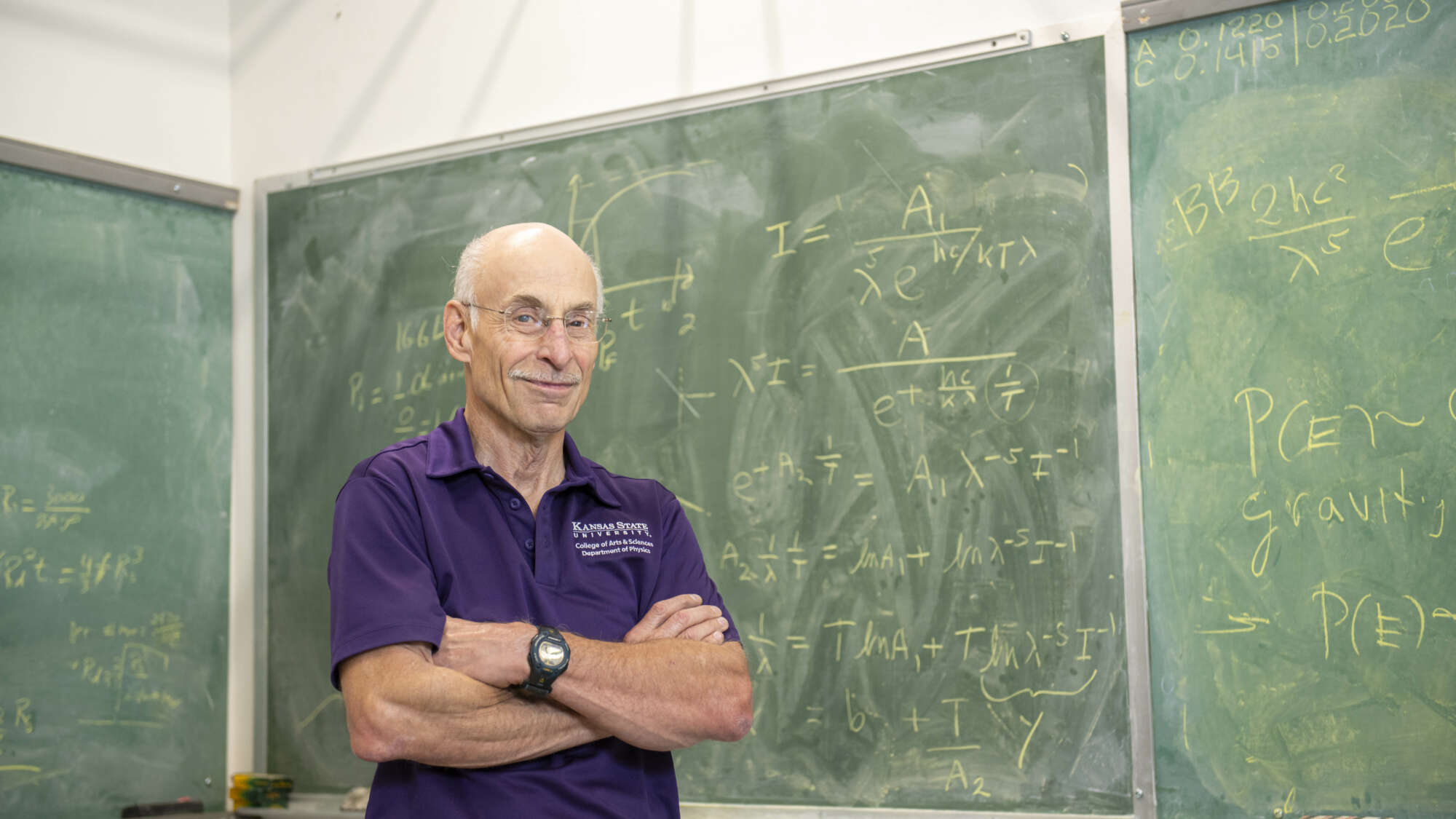

At universities large and small spanning the globe, it’s not common for educators like Chris Sorensen, K-State’s Cortelyou-Rust university distinguished professor emeritus of physics, to devote entire decades-long careers to one institution. But he’s one of the few who did, one of even fewer to reach undisputed expert status, and one of fewer yet to make the type of discovery that earns their institution international distinction.

K-State’s strategic plan identifies faculty recruitment and retention as a key priority, stating intentions to lead other land-grant institutions in developing a high-performing workforce.

But in academics, where competition for elite educators is stiff, is there a way to go about this scientifically?

Let’s conduct an experiment of our own.

K-State has a world-class educator in Sorensen — and was fortunate enough to have him for more than four decades. So how can K-State replicate this success story and attract more experts to our labs and classrooms?

Hypothesis

When financial support comes in the form of endowed chairs and professorships, K-State has an effective tool to help land the best of the best.

Data Gathering

Let’s collect what we know about Sorensen’s tenure.

Sorensen joined K-State’s physics department in 1977, shortly after receiving his Ph.D. at the University of Colorado.

He made a career-defining discovery in 2006, nearly 30 years later. Sorensen discovered how to create graphene — a material shown to make pivotal improvements to plastics, energy storage, concrete, and industrial lubricants — with a straightforward and inexpensive lab process involving the contained detonation of two gases.

“I was doing fundamental research to see if I could take fractal aggregates and make a gel out of them, which I managed to do,” he said. “But good fortune was on my side and when we looked carefully at the materials we made, we realized it was graphene.”

Before Sorensen, graphene production was a lengthy, hazardous and costly undertaking that required extracting and transporting graphite from mines across the globe and treating it with caustic chemicals at high temperatures.

Sorensen’s discovery has wide-ranging, international implications for the manufacturing of everything from high-demand semiconductors to cancer-detecting biomedical implants to green energy in the form of hydrogen gas.

“Graphene really is a marvelous material with spectacular physical properties — that’s why the scientists who discovered it in 2004 won the Nobel Prize in physics. But that was a long time ago, and everybody’s asking, ‘Why isn’t it hitting the marketplace?’” he said. “Industry’s answer is, ‘Nobody makes good graphene yet.’ Now we do. We’re new, but we make a product that checks all the boxes: It’s economical, high-quality, earth-friendly and scalable for mass production.”

“You could say we make the Porsche of graphene.”

K-State holds the patent for all this exciting potential. K-State students and faculty now have the advantage of developing scores of new products based on the discovery (several more patents are pending already).

Sorensen received many honors and awards. In 2007, he was named the Carnegie Foundation and Council for the Advancement and Support of Education United States Professor of the Year for doctoral and research universities. He won the Iman Outstanding Faculty Award for Teaching from the K-State Alumni Association in 2011, the same year he was named one of the top 150 scientists in Kansas history by the Ad Astra Kansas Initiative. He is a fellow of three scientific societies and past president of one. The list continues.

Recognition from peers, though, really resonated. In 2000 he received the title of University Distinguished Professor, in 2007 he received the Coffman Chair for Distinguished Teaching Scholars, and in 2009 he was named the Cortelyou-Rust University Distinguished Professor.

“There are a number of ways people think about being a scientist. And one way is the scientist working alone in the laboratory, diligently persevering despite failure after failure,” he said. “And that’s true, but then receiving the Cortelyou-Rust chair helped make it all worthwhile.”

Data Analysis

There you have it. Reviewing the research reveals it wasn’t the patents. It wasn’t the awards. According to Sorensen, it was the endowed chair that made K-State home.

“Sure, the chair allowed me to write small grants, but I think just the reassurance that somebody noticed I’m working really hard and being good at it helped me a lot. That’s huge.”

Curious about donors Mary Jo Cortelyou and John Rust, Sorensen found even more meaning in the award when he learned he shared so much in common with John — a fellow military veteran and passionate researcher in his own right.

Now retired and serving as vice president for research and development for K-State partner HydroGraph Clean Power Inc., the Canadian company who purchased the license to produce graphene using his method, Sorensen thought back over his career.

“It was significant to me to get that chair, and it’s essential to recruit and retain top quality professors. Over my entire 45 years, we have suffered for lack of facilities. And indeed, I lost good colleagues to other universities.”

Conclusion

Sure, we could put their name on a plaque, but take it from the experts themselves: K-State will stay competitive for top teaching and research talent by awarding endowed chairs.

And since we’re quoting philosophical physicists, here’s one more:

“Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.”

― Carl Sagan