As the nation’s housing shortage approaches crisis levels, a home-grown solution emerges from K-State’s award‑winning Net Positive Studio

The year was 2019, and Stafford County was hemorrhaging houses.

Years of careful economic development planning had paid off: The central Kansas county had employment opportunities to offer, but housing couldn’t keep up. How could it, when the county was tearing down four or more aging homes for each new one built?

As they joined countless other municipalities in this struggle nationwide, officials saw one attempted solution after another fall flat. They would need fresh ideas for long-term success, but where were those ideas hiding?

It turns out they were a short two hours away at Kansas State University, where the College of Architecture, Planning and Design had recently developed a program for graduate students known as the Net Positive Studio.

Curbing the crisis

The same question was stumping everyone: How can towns — large or small — grow when workers can’t find a place to live? Stafford County’s shortage of affordable homes left would-be residents with few options, limited to aging and low-quality dwellings.

“We have a housing crisis,” said Ryan Russell, Stafford County Economic Development executive director. “Population decline is a big concern for rural areas, and we’ve been fighting it here for a number of years already due to the lack of affordable housing.”

Why is a decent house suddenly so hard to afford? The problem is twofold: Houses are bigger and so are our energy bills.

Every house built in the United States for less than $150,000 was met with an average of 56 new homes costing more than $300,000 in 2020. And new houses have grown from an average of 1,590 square feet in 1976 to 2,333 square feet today.

Average residential electricity spending last year showed the largest annual increase since the U.S. Energy Information Administration began calculating it in 1984. The increase was driven by a predictable combination: extreme temperatures that raised electricity consumption for heating and cooling, and higher power-plant fuel costs that were passed on to consumers. Depending on a home’s insulation level, utility equipment and other factors, Kansans in 2020 spent an average of $2,677 on electricity and natural gas — with some hit with bills of $4,000 or more.

“We have a lot of staff in our school districts and our hospital who are coming in from outside Stafford County to work,” Russell said. “Our city managers field questions about where to buy houses all the time, but there’s just nowhere for low- to moderate-income residents to live.”

The county submitted a grant proposal for housing funds and hit the jackpot when the state connected it with Associate Professor Michael Gibson, faculty lead of K-State’s service-learning architecture course known as the Net Positive Studio. Gibson and his students would collaborate with community partners to research, design and construct a house that checked all their boxes in the county seat of St. John.

That pioneering-yet-pragmatic blueprint could serve as a prototype for a series of new homes throughout the county — and beyond.

Mastering a modern housing solution

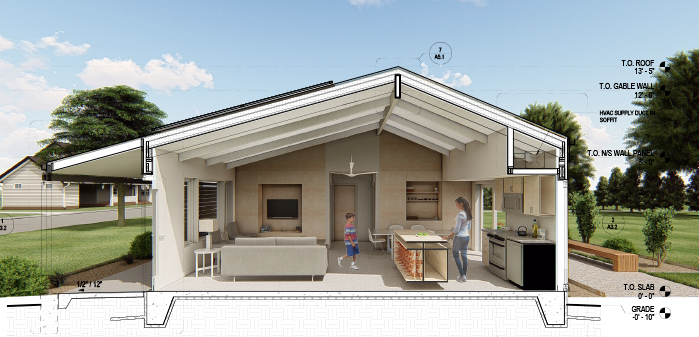

The students’ assignment seemed tough but straightforward: They would build a net-zero house. These homes are designed for net zero energy use thanks to strategies that maximize space and efficiency coupled with a small array of solar photovoltaic panels.

Having studied community–based development, Gibson knew the net-zero house was an important start. But he had seen what houses were capable of with a little extra consideration, and the studio was an important opportunity for his students — and the communities — to learn that net-positive homes were the path to a healthy, growing community.

“Housing doesn’t just need to save energy or sell for less: It needs to give something back,” Gibson said. “Housing needs to support comfort, safety, financial security, domestic life, social relationships and overall well-being for homeowners. Housing needs to achieve social and economic sustainability just as much as environmental sustainability.”

He established the studio in 2018 with support from Tim DeNoble, the college’s dean at the time, to offer students a real-world experience with a service slant. Instead of designing hypothetical buildings, these students would build actual homes that bring neighbors together and give the environment a break.

Creating real homes for real people is about as real-world as it gets, and it would give K-State students an experience that serves them well after graduation.

The studio delivers advanced research training to architecture students completing the final two semesters of K-State’s accelerated five-year master’s degree program. But Gibson sometimes wonders if the most valuable takeaway of the Net Positive Studio might be the thorough lesson in collaboration students are guaranteed to receive.

“Students in the Net Positive Studio are learning to communicate with clients, partners and stakeholders with a wide variety of skill sets,” he said. “No one on their own is going to build a net-zero, affordable house, but we can recognize each other’s strengths and do it together.”

That outdoor living space is essential to well-being is another tenet of net-positivity. The living area doesn’t end at the door; it expands to furnish the home with the restorative effects of its natural surroundings and encourages residents to be active in their community.

“Outdoor spaces also function as an extension of the house, and along with an open layout and high ceilings, make the surroundings feel spacious despite the small footprint,” Gibson said. “And that’s a testament to the creativity these students apply to the planning process — it’s imagination, persistence and passion.”

Learning to level up

The Net Positive Studio is giving new meaning to the word “homework.” In this one-of-a-kind experience, students work together to analyze everything from climate to the psychology of color, design a high-performance home and draw construction plans. Then they switch gears to pre-fabricate a large portion of the building.

Recent graduate Ann Lomshek studied sustainable landscape design and workforce housing extensively during her time in the studio, ultimately earning the Stella E. Ellithorpe award for student research. Now an architect in Dallas, she credits the studio experience with helping her get a great start to her career and deepening her passion for habitat restoration in residential design.

What does a sustainable landscape look like? Picture your summer to-do list: Cross out mowing. And watering, while you’re at it. Replace those lines with “sit on patio with lemonade and holler encouraging words at neighbors,” who are unfortunately still at the lawn’s beck and call.

“Replacing the traditional monoculture lawn with a native garden adds a lot to a net-positive house, because native plants eliminate the need for mowing and other maintenance that is often a hidden cost of homeownership,” Lomshek said. “I found that incorporating bioswales — a type of eco-friendly terracing — looks gorgeous and helps the property stand out in the community.”

The studio’s assignments require the advanced level of detail professional architects need on a design/build project of this magnitude. “Architecture students don’t often get the chance to build a realistic representation of their design, so our digital designs often exist mostly in our heads with no real confirmation that they could exist in the real world,” said fellow grad student Ethan Tschanz. “The Net Positive Studio teaches us to translate our work from the digital realm to the physical — a truly humbling experience, but one that will prove invaluable later in our careers.”

How smarter housing hits home

Creating modestly priced homes that improve lives and strengthen neighborhoods sounds like a tall order, but consider the prototype house in St. John: When the sawdust settled, the Net Positive Studio — along with AmeriCorps Vista members, Stafford County Economic Development staff and community volunteers — had built a 1,100 square-foot, $120,000 home that would be comfortable without heating or cooling for more than half the year.

With 30% of take-home pay as the threshold for an affordable housing cost burden according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, a homeowner earning $37,660 would need to cap monthly payments at $827 or less. The owner of the K-State house would only pay an estimated $720.

“Through this process, we’ve learned that a well-designed, compact house requires only a modest amount of solar power to offset — or even exceed — the amount of energy it will use,” Gibson said. “We’re demonstrating that good design, analysis and construction will enable almost anyone to afford a net-positive house.”

Skeptics need only look to the U.S. Department of Energy, which awarded the St. John student design team with second place in the market potential category, third in the architecture category and third in the affordability and financial feasibility category of the Solar Decathlon 2020 Build Challenge, a collegiate competition to build high-performance, low-carbon homes powered by renewable energy.

Or they can look to Stafford County — now the location of 10 additional homes based on the K-State prototype — and to Ogden, Kansas, which became the site of a net-positive house in 2021 that’s now home to Yackelyn Torres and her family. “When someone is struggling with poor living conditions, it can make a world of difference to transition to homes like these,” Stafford County’s Russell said. “The better-quality surroundings, with their natural light and low-stress energy costs, translate directly into better-quality lives.”

Proving it’s possible

Now that Gibson and team have arrived at a solid system for single-family dwellings, they’re branching out to create entire net-positive communities. The studio is working on a project that could become a development of 16 to 18 net-zero homes in Ogden. Gibson is also considering larger multidisciplinary efforts with landscape architecture and community planning counterparts.

The homes in Ogden and Stafford County are shining examples of K-State living its land-grant legacy. The Net Positive Studio’s ingenuity can be scaled up to strengthen communities in a way that’s good for students, good for the university, good for the economy, good for the environment and good for Kansas.

“So few homes are being built to meet sustainability goals yet remain affordable — you really don’t see that combination very much anywhere, especially in Kansas,” Gibson said. “We’re doing this to prove it can be done.”

Keep the progress going

Support fellowships for fifth-year students

K-State is working to become the first nationally ranked architecture school to cover the cost of its final year. Help power the College of Architecture, Planning and Design’s fifth-year fellowship program, so students can devote their time and creativity to pivotal experiences like the Net Positive Studio.

Give to fifth-year fellowships

Project collaboration

Collaboration has been key to the success of builds in the Manhattan area since 2020, where the studio joined Manhattan Area Technical College, Flint Hills Renewable Energy & Efficiency Cooperative, the Home Builder’s Institute at Ft. Riley, and Manhattan Area Habitat for Humanity to create the Workforce Solar Housing Partnership and promote net zero development in disadvantaged communities.

The Ogden project was funded by the Goldstein Foundation and the Greater Manhattan Community Foundation.